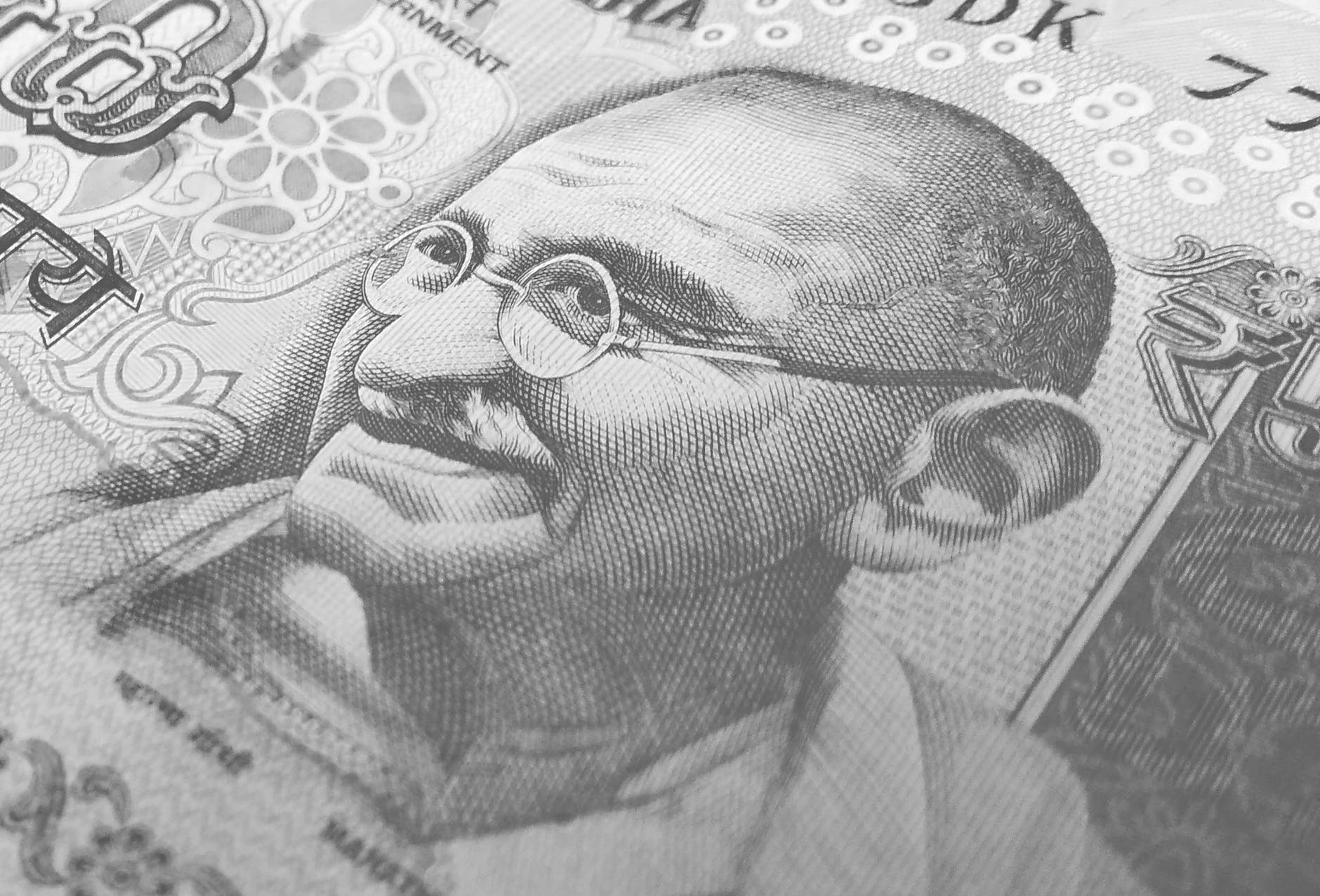

Explore the intricate life of Mahatma Gandhi in the context of India and Pakistan’s independence in MJ Akbar’s book ‘Gandhi’s Hinduism: The Struggle Against Islam’.

On August 14, Pakistan celebrated its day of independence. The following day, India won its independence. These were, however, days of “heartbreak” for Mahatma Gandhi, the finest soul to have ever lived among Indians and Pakistanis. Because of the pain he felt for the people discriminated against in both countries, he decided to spend August 15, 1947, in Pakistan and eventually make that country his home. Gandhi’s Hinduism: The Struggle Against Islam is a superb examination of Gandhi’s life written by the well-known author MJ Akbar and published by Bloomsbury. In it, Akbar reveals a previously unknown secret that had been kept hidden.

It was not a matter of tokenism, contrary to what many people may believe, but Mahatma’s conviction. “He felt that faith might promote the civilisational harmony of India’s many different religious traditions..He did not think one’s religious beliefs might impose arbitrary boundaries within a nation… According to the book, his main interest was with the people directly affected by the partition: the Muslims and Hindus living in India and Pakistan.

According to the book, Gandhi intended to prevent another incident like the riots in 1946 at Noakhali, located in East Pakistan. He wanted to do this by being there. Gandhi was still working hard to salvage some glimmer of optimism from the ashes of sectarian violence, believing that Hindu-Muslim harmony would one day be restored and triumph.

According to the book, on May 31, 1947, Gandhi disclosed to Pathan leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan, also referred to as “Frontier Gandhi,” that he intended to travel to the North West Frontier and reside in Pakistan after the country achieved its independence. I wonder why the government should be split up this way.

I am not going to bother anyone for permission to do this. I will gladly welcome death with a smile if they want to kill me due to my defiance. The book cites him as saying, “That is, if Pakistan comes into existence, I intend to go there, tour it, live there, and see what they do to me,” this is precisely what he plans to do.

According to what is stated in the book, Gandhi’s moral stance did not suddenly appear out of nowhere; instead, it was maintained throughout the protracted and tumultuous roller coaster ride of high-voltage events.

Over more than half a century, he sang every song from the same hymn sheet. According to the hymn that he was singing, religion is a catechism of love, tolerance, and unity. Whether he was in South Africa or India, for more than half a century until the end of his public career in 1948, he explained why he was glad to be a Hindu, as the book reveals. “He explained why he was proud to be a Hindu.”

The author attributes the writer’s interpretation of Gandhi’s life and politics to the author’s belief that Gandhi received a religious upbringing in his childhood home. He was a member of the Pranami Sampradaya, which was established in the 17th century by Devchandra Maharaj (1582-1655).

This school of thought emerged when the Mughal emperor Akbar’s reformist policies energised the expanding Mughal domain with new amity between the predominantly Hindu population and the largely Muslim ruling elite. Kuljam Swaroop, a scripture of Pranami Dharma, was composed when one of Devchandra’s pupils, Mahatma Prannathji (1618-94), travelled through the countries of Oman, Iran, and Iraq. The Bhagavad Gita, the Vedas, the Quran, the Bible, and the Torah are all represented here.

These Pranami ideals were presented to Gandhi each morning with breakfast by his mother, Putlibai. She instructed him that all religions sprang from the same eternal source and that the Vedas and the Quran are heavenly texts. Putlibai was Gandhi’s mother. The young Gandhi imbibed and preserved these syncretic principles as if they were his most treasured possession, and as a result, they had an enduring, profound, and lifelong influence on him.

When Gandhi assumed the role of leader of the liberation movement in India, he began his prayer sessions by reading passages from all of the primary religious scriptures. As part of the prayers offered by people of many faiths in his ashram, he recited the first chapter of the Quran, known as the Surah Fatehah, which praises the Rab Al Alamin, also known as the Lord of the Universe.

According to Akbar’s writings, Gandhi’s personal and political life was fused with humanism. This humanism held the belief that the unity of India lay in the acceptance of religious and cultural diversity and that India’s geography was a natural evolution of shared space between Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, and Parsis or indeed any community that had made this vast subcontinent its home.

According to the evidence shown in the book, he often asserted that “I am a good Hindu and thus a good Muslim and good Christian as well.” On one occasion, he stated in front of an audience that if the Prophet Muhammad were to come to earth now, he would discover in him a better Muslim than the majority of Muslims and that if Jesus were to descend from heaven, he would see in him an ideal Christian than in his followers. These statements were made about the possibility that the Prophet Muhammad and Jesus might meet.

This portrayal of Gandhi as a genuine adherent to the tenets of multiple faiths is only one of many that can be found throughout the book. According to the book, several of the leaders of the Muslim League see Gandhi as a Mahatma, also known as a beautiful soul or darvesh.

Despite enormous opposition from several extremist organisations in India, he insisted that Pakistan be given its rightful portion of the treasury by his moral and political ideals. This was done even though the opposition was overwhelming. However, he did not flinch and instead gave his life to Pakistan before being killed by a gunshot.